The Interpersonal Tragedy of China Decoupling

The case for enduring friendship between Chinese and Western people

I’m sad to leave China after spending much of April there. It’s expected to feel loss at the end of any trip, as you truly are leaving a place and the people that you have spent the last weeks forging connections with. However this is different, because it isn’t just me who is leaving China, but China itself that is drifting away from the rest of the world. I met this conclusion numerous times throughout my recent visit. It’s been three years since I first remarked on the “new Cold War” between China and Western allies, and the human-to-human cost wrought by isolating Chinese people from the rest of the world is an immeasurable loss for all people.1

China is an amazing civilization. Its history and culture are astoundingly deep and complex. Trying to grasp the immensity of China’s culture is like standing at the base of a mountain with your nose against a cliff wall and trying to guess its height. You could spend a lifetime studying it, and just scratch the surface. And, I often found myself naive to elaborate Chinese culture, as I made missteps around gift giving/receiving, intricacies and expectations of multi-generational relationships (“guanxi,” 关系), drinking culture, and much more. There is a lot to celebrate about Chinese culture: incredible art, music, lore, cuisine, gardens, temples, language... There is likewise a lot to marvel at in the post-revolutionary “New China”: huge beautiful museums and airports, fast clean trains that span the whole country, a prosperous middle class, cities rich with amenities and largely free of the dysfunction we normalize in the West (crime, homeless encampments, spotty infrastructure, etc). Especially in Shanghai, I encountered a society of nearly decadent abundance, where anything can be delivered in an instant, where the best of everything was everywhere, and where a raucous nightlife was paired with clean and quiet neighborhood streets ideal for a young family.

More than their flashy night clubs and marbled halls, the people I met in China were incredible. I encountered none of the nationalist bravado that we are conditioned to expect on social media. I attribute this largely to barriers to ordinary Chinese people from joining global social media apps, so voices are instead concentrated on the appointed nationalist “wolf warriors.” Rather than geopolitical ambitions, the people I talked with were focused on the well being of their own families and communities. This perhaps is the learned behavior not just from living in a country that prohibits politics, but also the multigenerational lessons of history itself: many young people have grandparents who survived the upheaval of the Cultural Revolution, parents who lived through the 1989 protests, and young people themselves as witnesses to seemingly endless draconian pandemic lockdowns.

That said, there is surely some selection bias in the people I came across, despite my best efforts to break out of it. There are likely many people at the base of the pyramid who I would never cross paths with and who have no access to a VPN, only consume state media, and are as nationalistic as instructed. Nevertheless, I didn’t come across this, even in the smaller cities I visited and when traveling with local friends away from tourist destinations, or when asking friends about how their parents feel about issues.

There is a lot of mutual admiration between Chinese and Western people. We both belong to essentially capitalist systems, despite insistence on the contrary. The Chinese people I met were very curious about the outside world, and they all routed around the Great Firewall with VPNs on a daily basis to access it. Likewise, the world is curious about China. There were once plentiful flights each day from all major cities in the USA and China. The USA, Europe, Canada and other countries have a sizable Chinese diaspora. Chinese people, Chinese culture, Chinese history, and accumulated Chinese wisdom all enrich the lives of those of us in the West, just as I would expect the Western experience informs those who live in China. We were better off when this human-to-human exchange was flourishing.

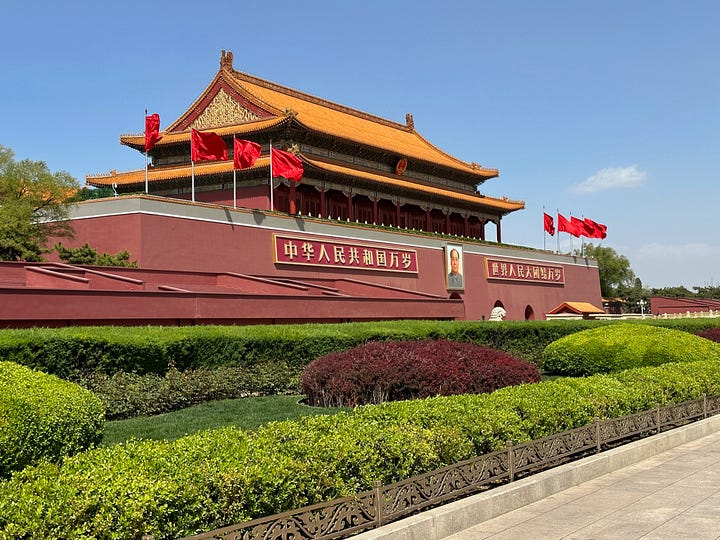

The glory days of this flourishing are in the past, but I got to experience bits of what’s left. I visited a premier university in Beijing that was partially designed by Americans and once had wings named after US Presidents (names since removed). I stayed at a government resort on Hangzhou’s Xi Lake that was the site of the 2016 G20 meetings. I toured venues and nightclubs that are part of the spectacular Shanghai nightlife and once home to many foreign musicians on dubious visas.

Visiting China today is very difficult, and trending worse. US-based airlines currently offer just twelve flights per week to China. Worth reiterating: that’s twelve flights total, spread over seven days from all American airlines between the two largest economies in the world. This is just 6% of what was available in 2019. Efforts to resume flights have stalled over disputes about the advantages Chinese airlines have by being able to fly in Russian airspace.

Without local friends in China, I never would have been able to truly experience the country. All commerce happens via WeChat and AliPay. It is essentially impossible for non-Chinese citizens to use WeChat for payments, as a Chinese local bank account and ID verification is required, and often a Chinese SIM card as well. Even Hong Kong bank accounts (like HSBC) won’t work unless they are local accounts based in mainland China. Yet WeChat is where the staples of life happen: ride sharing, train tickets, and even the mandatory airport health declaration all happen on WeChat. I eventually was able to get AliPay to work in certain situations, especially after I traded bitcoin for AliPay CNY from a local friend. Travelers also have to know to either purchase and install a VPN prior to arrival (which requires constant troubleshooting) or use cellular data roaming. Staple services like Gmail, Google Search, almost all ex-China social media fail to work on domestic wifi without a VPN. Even Google Translate—an essential travel tool in any foreign country—was recently banned in China. And add to all of this the vast security complex of the Chinese state: I probably scanned my passport and/or was frisked 50 times during my two week trip including 4 times just to enter the (beautiful and expansive) National Museum adjacent to Tiananmen Square.

With vanishingly few flights to China, an inaccessible system for basic financial transactions, severed contact to the outside internet, and an omnipotent security apparatus—it is easy to conclude that the country doesn’t place a priority on its visitors. Yet, I had an amazing and impactful trip to China in spite of these things and thanks to close friendships I’ve made over the years (and some new ones made during the trip). As an American, I certainly have no entitlement to a red carpet experience in another country. Yet having traveled to many friendly and adversarial countries (including two other Communist countries—Cuba and Vietnam), I’ve come to rely on the basic ability to use cash, access the open internet, and not need to be shoehorned into an “everything” app that returns errors in another language.

And the human-to-human decoupling is happening well beyond tourism: it is at every layer of society. Harvard once had an intensive Chinese language program in Beijing that recently closed and moved to Taiwan “due to a perceived lack of friendliness from the host institution [in Beijing].” Among other things, American students in Beijing were prohibited from celebrating the Fourth of July. The US State Department advises American visitors to “Reconsider Travel” due to arbitrary detentions. Indeed, China recently broadened the scope of its espionage law and raided the offices of the top US consultancy firm, Bain & Co.

China is turning inward, and all of us are worse off as a result. China and Western countries are pitted against each other in an increasingly dramatic confrontation. The origins of this conflict is a list growing ever longer: human rights, Taiwan, IP, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the South China Sea… Yet the human beings in these countries are decent people with shared values and mutual empathy and curiosity. And if these bonds of friendship are strained by an inability to simply meet—online or as visitors in each other’s countries—then we shouldn’t be surprised when this mutual goodwill evaporates. My hope is that we resist this however we can: by insisting on travel even when it is uncomfortable, by going out of our way to make new friends across cultures, by using VPNs and routing around barriers, and by engaging with local diaspora communities. As individuals, our impact on the great power conflict between the US and China is limited, but the relationships we forge with each other will outlive any geopolitical fallout.

A friend reminded me of this quote, which was a marriage contract between two Chinese scholars, 张爱玲 and 胡蘭成. It should also be a shared aspiration of all people and nations, albeit an ever distant one today:

“岁月静好,现世安稳”

“The years are quiet, and the world is stable”

Disclaimer: I was a visitor in China. I am not an “expert” nor a “China watcher” nor Chinese and this is simply my personal reflection as a single curious individual. This isn’t a scientific or systematic study, but just my loosely held impression based on a short trip, informed by my Chinese friends and former classmates in America, and my past trips to nearby Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan. It also isn’t an examination of the origins of the poor relationship China has with the West, which includes many serious issues worth their own article.

Amazing work brother.

Wow, thank you for writing such a nice piece. As a Beijinger, I'm touched. It made me homesick. This is exactly the kind of conversation needed to happen if we are to progress as a whole. Mutual understanding, respect, and conversation are the keys. I'm crossing my fingers for that day.