I'm cute I'm punk rock

The frenzied path out of Dimes Square to Network Spirituality

The punk rock movement of the 1970s came at a time of peak societal upheaval, as manifested by the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement, Women’s liberation, and Watergate. Punk rock as a counter-culture was a natural reflection of this discordant time, and punk rockers went to extreme lengths to demonstrate their rejection of societal norms. For example, art critic Dan Graham wrote about this phenomenon in his essay “The End of Liberalism,” describing how punk rock ironically used fascist imagery like the Swastika or album titles like The Resident’s “Third Reich ‘n Roll” as a forceful rejection of the “‘mellowed out’ fantasies recollecting the ‘good vibes’ of the 60s.” These taboo allusions predictably drew out the condemnation of polite society, and the punk rockers reveled in their newfound infamy and planned their next act of performative transgression.

Our current societal moment has been likened to a “new 1970s” by writer and economist Noah Smith, and fittingly there is a new subculture with a similar transgression feedback loop that I will call “ex-Dimes Square culture,” named after the New York City microneighborhood where it began in 2020. Dimes Square is just a few subway stops away from the origin of punk rock in Manhattan’s East Village. The Dimes Square neighborhood is notoriously over-analyzed: it’s the subject of countless exposés relative to its small triangle of streets, restaurants, and handful of microcelebrities. To summarize, Dimes Square is an unofficial microneighborhood in Chinatown that from 2020 to 2021 incubated its own reputation of (depending on who you ask) either post-political avant garde cognoscenti, or less charitably as fashionably ironic reactionaries. It’s a subculture that its members themselves are sometimes uneasy being associated with, as an attendant at a local Kabbalah-specialized bookstore told me that even the purveyors of the “Dimes” restaurant (after which the square is named) prefer not to use this moniker and instead opt for the official title of “Chinatown.”

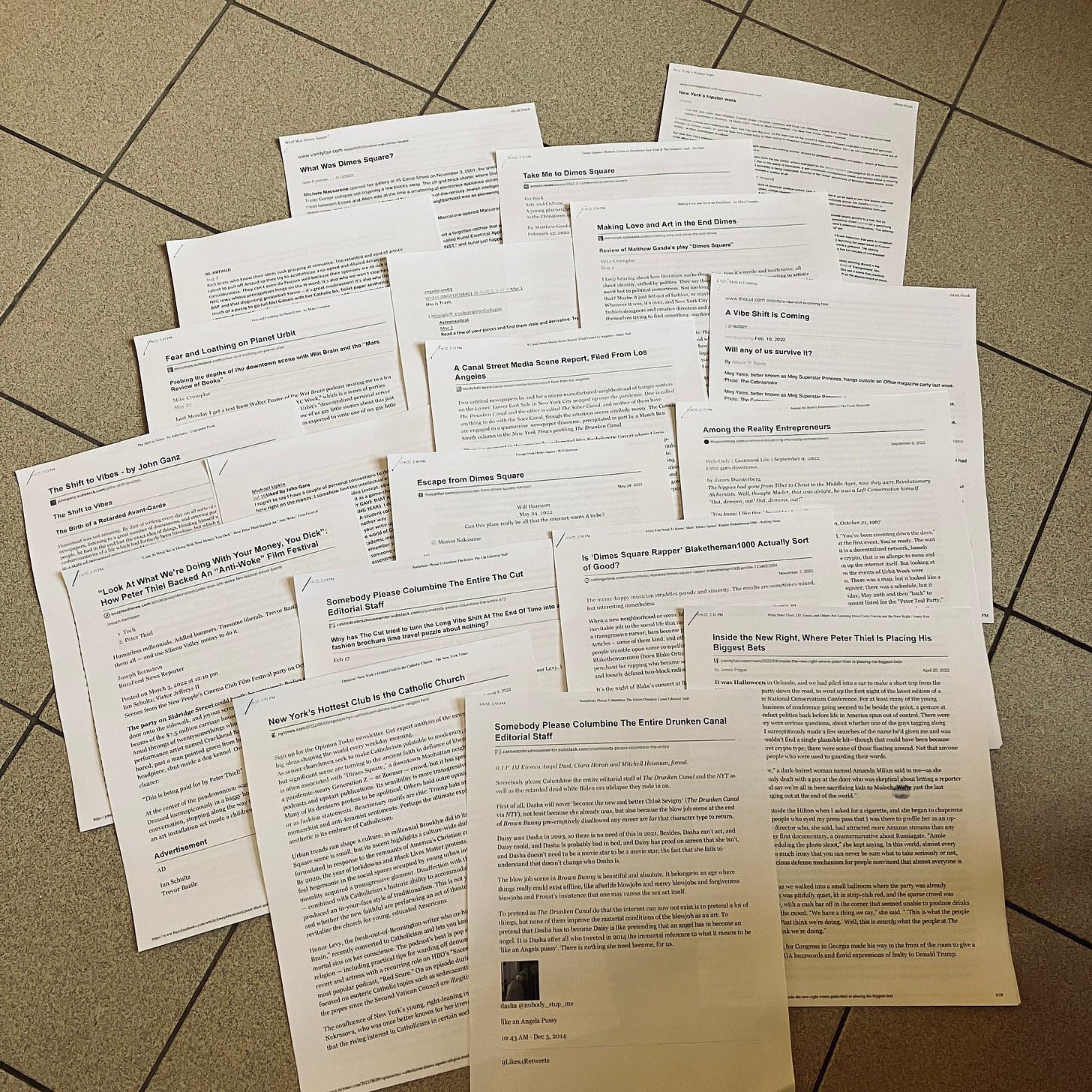

The Dimes Square scene has several defining characters and a self-referential mythology. There is actress Dasha Nekrasova of the contrarian “Red Scare” podcast and her various appearances in liberal-minded press (the New York Times commented on her newfound Catholicism in a piece describing an emerging “contrarian aesthetic [and] its embrace of Catholicism”, and the New Yorker on a party she attended with the pardoned felon and Trump acolyte Roger Stone), and there’s Sophia Vanderbilt who is a very-online socialite who contributed to the Milady Maker NFTs, there’s the defunct indie newspaper the “Drunken Canal” referring to nearby Canal Street, and the schizophrenic-stlye blog of angelicism01 known for such posts as “Somebody Please Columbine The Entire Drunken Canal Editorial Staff,” and writer Honor Levy and casting director Walter Pearce who together hosted the “Wet Brain” podcast.

The Dimes Square scene peaked amidst 2020 lockdown breaking parties, but as rent prices increased post-Covid (even a luxury hotel opened), many of the creative types central to the scene moved back to Brooklyn. Some cultural commentators even declared the movement dead. The reality is that Dimes Square was always a fusion of neighborhood and internet culture, and as the neighborhood gentrified, the online portion became the dominant component. In fact, my estimation is that the online “ex-Dimes Square” culture has far surpassed the impact the neighborhood itself. This leap from the microneighborhood to the viral and constantly metamorphosing online art movement is the basis of this essay.

Even this whirlwind tour of Dimes Square highlights a few of the themes from this emergent subculture. Irreverence and transgression are crucial: Red Scare and angelicism01 make liberal use of the pejorative “retarded” seemingly just to remind you that they aren’t beholden to prevailing norms. Red Scare co-hosts ironically call each other “fascists” and adulate various authoritarians, but meanwhile have immense cultural fluency--discussing the Freudian themes of the anime series Neon Genesis Evangelion or recent political events (eg, the “CNN Clown Hall”). There is an ironic religious adherence, especially to Catholicism. Converts to Catholicism brandish it as “my Catholic arc,” or being “God-pilled.” The anonymous anglecism01 blog that called for the “Columbine”-ing of editorial staffers uses a quintessential “schizoid” style that, while enthralling and poetic, can also feel inaccessible. The subculture is also extremely self-referential: there is a small cast of characters that are constantly being self-cited as if to reinforce their own “lore” or neighborhood mythology.

Angelicism01 is most renown for popularizing the “vibe shift” neologism, which referred to a few days in June 2021 where its proponents assert there was a cultural shift not only in their Dimes Square scene, but also across the internet. Indeed, the Remilia Collective (behind Milady Maker and other art projects) described the vibe shift as a “contemporary phenomenon of radical pivots in culture self-organized almost instantly and without a single specific catalyst by small groups of intimately engaged posters--a phenomena only possible in the network era.” The vibe shift was subsequently reported by major media outlets (eg, New York Magazine’s The Cut), causing the Dimes Square microcelebrities to bristle at the attention while simultaneously jockeying over who was and wasn’t cited and the precise dates the vibe shift happened.

The Remilia Collective is best known for its Milady Maker NFT collection from the summer of 2021, which has been the source of adoring fans and waves of controversy and cancellation following the familiar punk rock transgression feedback loop. Milady NFTs are cute anime profile pictures that flirt with transgression by, for example, ironically referencing 9-11 or the Japanese “hikikomori” concept of incel culture. The images may appear lighthearted and simplistic at first glance, but there is tremendous depth to the project. For example, angelicism01 (ever the spiritual inspiration of ex-Dimes Square culture) analyzed the Milady project in the context of Landian accelerationism.

Apart from the images themselves, there is a thriving internet culture of posters who “wear” the Milady profile picture and seek virality (often successfully), brigade posts, and post ironically in the voice of the girl in their profile picture. Members have a certain affection for their various “cancellations” over the years, ironically self-identifying as a “pedo groomer pro-anorexia death cult,” though their disposition to these domains seems mostly performative and self-mythologizing. Although it may not be immediately obvious to the casual web surfer, this is a kind of online performance art acting as an extension of the image collection.

Rather than dwell on the Milady NFTs (like Dimes Square, too much has already been written), there is a more recent derivative work called SchizoPosters that advances new concepts in this constantly evolving subculture. SchizoPosters follow the same general aesthetic of the Milady NFTs, but feature overlaid text and diagrams that draw heavily from conspiracy theories, the occult, infamous 4chan copypastas, and self-referential lore from the various Discord servers and other enclaves where this culture is incubated. These texts and diagrams are overlaid in their defining schizoid aesthetic, as if part of a conspiracist’s white board, drawing frenzied arrows between imagined concepts and events. For example one such SchizoPoster has a schematic of an MP5 machine gun in the right corner, the entire left side covered with a web of arrows connecting concepts of the occult (“Church of Satan,” “L. Ron Hubbard,” “Ark of the Covenant”) and conspiracies (“Area 51,” “vaccines,” “Monsanto,” “Reptilians,” “Black Goo”), including some clearly transgressive references (“Protocols of the Elders of Zion”), and the right side with various 4chan and reddit copypastas (“A Girl AND a Gamer? …”).

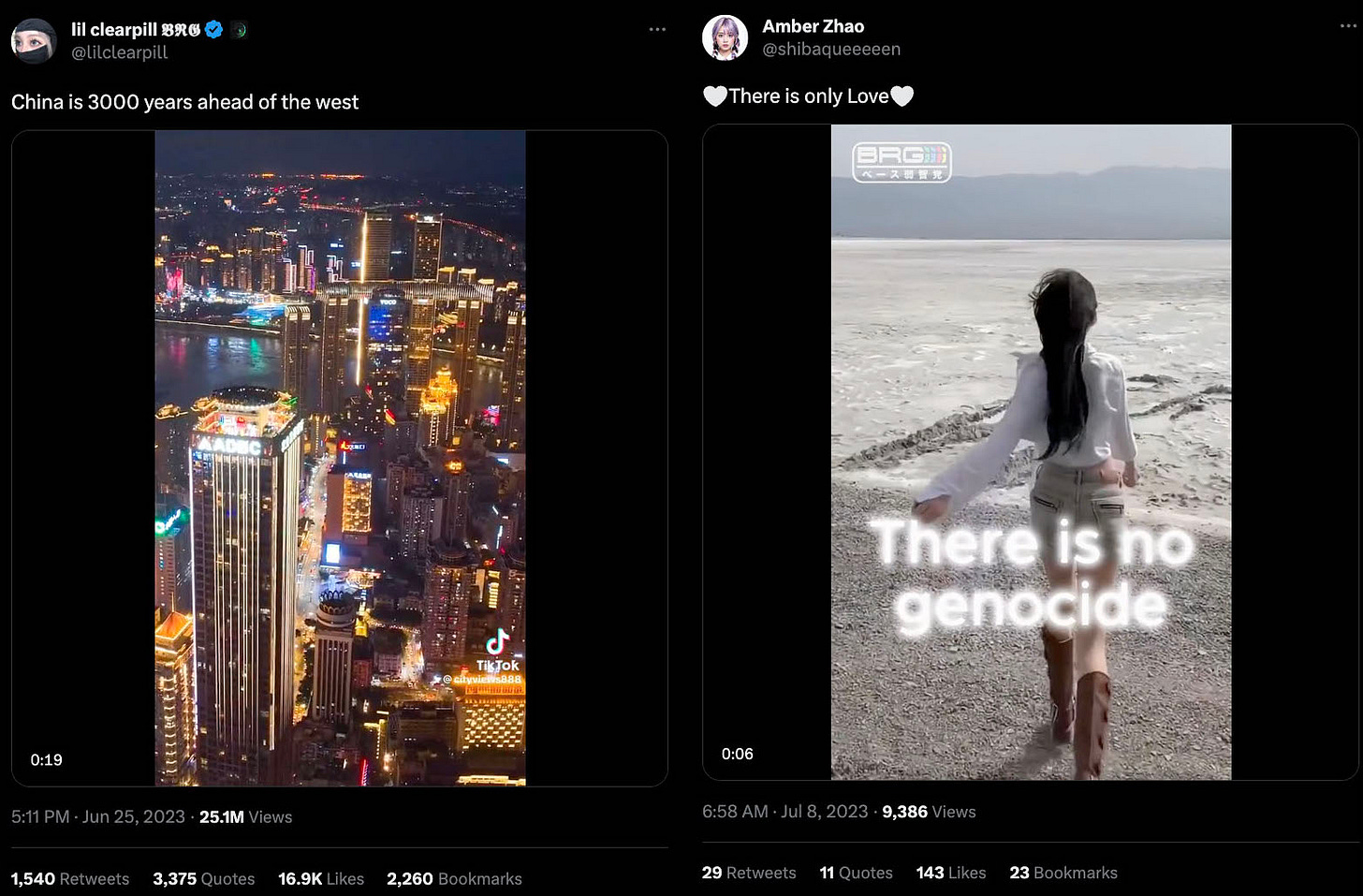

The schizoid aesthetic of these images is enthralling and each one is an invitation to fall down a rabbit hole uncovering a trove of lore from scattered dark corners of the internet. Many images also lean into East Asian themes, with overlaid text in Chinese or Japanese. In fact, the East Asian theme becomes a central focus in the most recent iteration of this subculture, called “Based Retard Gang” or #𝔅ℜ𝔊. Rather than don a Milady or SchizoPoster profile picture, these posters take on the persona of an actual Chinese girl, usually borrowing pictures from the Chinese social media site Xiaohongshu (“Little Red Book,” 小红书). Whereas with SchizoPosters the art is in the image, BRG is entirely an online performance art. Posts again are primed for virality by making wild claims (“China is 3,000 years ahead of the West” with a stylized video of Chongqing borrowed from TikTok) or norm-breaking (a video from Xinjiang with, “There is no genocide, just LOVE”). Almost programmatically, these posts attract viral infamy (the “3,000 years” post is at 25 million views and was picked up by anti-CCP accounts) thanks to amplification from outraged “normies” sparring with brigading community members.

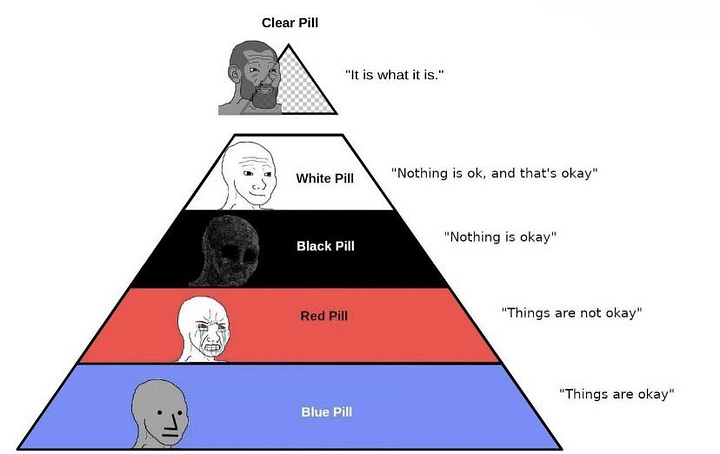

Another theme popularized by the Based Retard Gang is the concept of the “clear pill.” You may have come across the popular Matrix reference of “choosing the red pill or the blue pill,” referring to the choice between seeing reality as it is (“red”) or the comforting naivety of the world that is presented to us (“blue”). The clear pill is a radical acceptance of societal chaos, considered by its proponents to be a more enlightened perspective than those who maintain worldly concerns. This embrace of chaos, paired with futuristic orientalism, is the basis for BRG-style accelerationism.

Accelerationism is a recurring theme in ex-Dimes Square thinking, as it was foundational to the Remilia Corporation (specifically kali-yuga accelerationism, or “kali/acc”), and similarly ascribed to angelicism01. Accelerationism has many varieties, but one popular version is the idea that the only way to overcome our current (“fourth turning” or “black pill”) societal breakdown is through a devastating calamity on the order of the nuclear bombs in WWII or the US Civil War. These accelerationists don’t just accept the inevitability of such a calamity, but push to bring it about more rapidly so that we can “exit” to the tech utopia on the other side. Other accelerationists focus less on “exit via calamity,” and instead see tech advancement as messianic, ushering in the Singularity. For the Based Retard Gang, utopia is a glimmering cyberpunk Chinese megacity that is “3,000 years ahead of the West.”

The phrenetic path out of Dimes Square to the Based Retard Gang is a constantly metamorphosing and decentralizing art movement. The only constant seems to be the transgression feedback loop from the old punk rock days: bask in the outrage from the normies as you plan your next transgression. Some observers have eulogized Dimes Square, and they are right that a lot of the original creatives have left as the neighborhood gentrified. What they miss is that it endures (thrives, in fact) online as a kind of transcendent “Network Spirituality.” While some of the original Dimes Square cohort have dropped off, other key figures remain even in this digitally native iteration. Even newcomers that I spoke with in the Based Retard Gang pointed to the original Angelicism01 posts as their “inspiration to create.” Remilia raves are now in Tokyo and Paris, and even included a recent online-only “Grand Ball” on a Minecraft server that (in the classic transgressive style) featured a mock mass shooting.

Ex-Dimes Square culture is maturing as it decentralizes. Artists with ties to the neighborhood are now displayed in New York’s premier museums. Elon Musk is posting Milady memes and Grimes is sorting through the various controversies. Even this article is as an effort in intellectualizing a freewheeling culture. And as it matures, the irony itself is better understood as way to “try on” different accelerationist philosophies with plausible deniability rather than as purely performative.

The art is alluring and like punk rock, it can be enjoyed ethically even among those of us steeped in “normcore” sensibilities. Yet there is an instructive challenge from the 1970s on performative transgression: not everyone understood the irony of the punk rockers and their fascist imagery, and when the true neo-fascist skinheads arrived on the scene, the movement had to push back (eg, through efforts like the Clash and Sham’s “Rock against Racism”). Of course, such moderating efforts break the transgression feedback loop, and for punk rock that diluted the style to the more socially acceptable “New Wave” genre in the 1980s. Alas, we are still firmly in the ‘70s arc of the ex-Dimes Square subculture for those who seek to plunder the depths of the rabbit hole, to achieve Network Spirituality, or to be outraged by it.